Estonia is an educational powerhouse. But how did a small, relatively poor European nation, with a limited international presence come to be so?

In 2022 Bridget Phillipson, the UK’s new Education Secretary, visited Estonia to find out what makes this education system tick. This blog post will explore what she might have learned and in turn how this might shape thinking about UK education policy going forward.

Estonia ranked first in Europe in the 2022 PISA results, an international test that seeks to compare education systems around the world in Maths, reading and Science. Worldwide the nation placed 8th[i], behind only a handful of highflyers from Asia. It has the smallest percentage of low performing students in the world[ii] and more top performers than the OECD average[iii].

Socioeconomic status as a predictor of educational attainment was one of the lowest across the OECD, highlighting great success in supporting disadvantaged students[iv].

Beyond purely academic success, Estonian teachers reported high levels of job satisfaction[v]. Student dissatisfaction with education and discipline issues were both well below the OECD average. Moreover, Estonia ranks as one of the highest in the world for levels of individual school autonomy, and this is a key metric behind high performing school systems.

All of this amounts to Estonia’s education system being the envy of the world. But what factors contribute to its success? This blog post outlines several important elements ranging from a comprehensive provision of early years education to a high degree of autonomy for schools and teachers.

Early Years Education: the Foundations of Success

In Estonia students do not start formal schooling until they reach the age of 7[i]. Until this point, and from as young as 18 months, they are in kindergarten. The main aim of this stage is to minimise differences caused by disadvantage when they reach school[ii].

Kindergarten gradually introduces students to learning whilst allowing them to have fun[iii]. Play is directed by teachers, and this ‘fun’ learning ensures that all children are emotionally and physically ready for the start of their formal education. Many similar skills taught at this age in other education systems still take place in kindergarten, but in a more relaxed, playful environment[iv]. Most children enter schooling with strong reading and writing skills for example.

Estonian early education centres follow a national curriculum that focusses on 7 aspects of development including social skills, arts, music, movement, language and mathematics[v]. Students participate in two lessons per day in small groups for guided instruction[vi].

In the UK students already take their first examinations by the age of 7. In contrast, Estonian children are not graded through tests. They simply get a school readiness card describing their skills, development and targets for progress[vii].

Furthermore, kindergarten ensures early access to assessment and therapies for SEN, aiming to identify and address any issues before students reach formal education[viii]. There is a maximum wait time of 70 days for an initial assessment, which is undertaken inhouse within school. If therapy is recommended, extra funding is soon provided to allow this[ix].

Kindergarten teachers are required to have a bachelor’s in early childhood education, a far higher standard than in most other countries.

Every child receives this municipally funded early years education, with parents only contributing up to 70 euros per month[x]. Children are at kindergarten for 12 hours each day[xi] and 90% of all eligible children in Estonia are enrolled in early years education[xii]. This extensive early years provision helps to grow the economy by allowing parents to work more.

Estonian mothers hold the right to three years of maternity leave, during which their employers must guarantee their position. For the first 18 months, they are also expected to receive a full salary[xiii].

Early years provision in Estonia is drastically different to that seen in the UK. But the result is clear to see by the fact that by the age of 15, Estonian students are significantly outperforming UK students in every subject assessed by PISA[xiv].

In the face of a crumbling early years sector in the UK, emulating the Estonian model was a key motive behind Bridget Phillipson’s visit in 2022. As I explored in a recent blog post, the Labour manifesto committed to expanding the early years provision available to parents.

All of this amounts to a world class level of early years education that contributes heavily to the success their wider education system enjoys.

Educational Equity and Inclusivity

Threaded through the Estonian education system is the abiding principle of equality[i].

The nation has among the most equitable outcomes of all PISA countries, with socioeconomic background accounting for a smaller attainment gap than the OECD average[ii]. Driving this is a clear philosophy that education is a tool for a better life and self-improvement for all students[iii]. For example, Estonian schools avoid over testing students, with the aim being simply to help every learner fulfil their potential.

Whilst early years education is heavily subsidised, all children are also entitled to free high-quality schooling too. Only 5% of all schools are private[iv].

School lunches, textbooks and transport are provided for free[v]. Every school has a psychologist or counsellor[vi]. If students need extra support above this, it is readily available.

Inclusive teaching is practiced and trained for, with SEN students usually being placed in ordinary classes[vii]. In line with this, mixed ability classes are the norm with setting shunned as a concept[viii]. The onus is placed on their highly trained teachers to find ways to level up all pupils regardless of their backgrounds.

After independence from the Soviet Union, Estonia based their new education system on the renowned Finnish model which prioritises equality. Estonia has subsequently viewed equality in education as the precursor to success.

Innovative Teaching Practices

The high ranking of this education system is in part thanks to the forward-thinking attitude of educators.

There is only a limited hierarchical structure within schools, with students and teachers being treated almost as equals. Independence is given to students which allows them to learn in a relaxed environment conducive to individual excellence.

A child centred teaching approach finds out what each student is good at and homes in on this to bring out any individual strengths. In line with this, discovery-based learning is king. Students regularly guide the direction of their own study.

Students are taught about mindset and how to learn. They learn about the psychology of teenagers, why learning may appear difficult at times and how to achieve despite this[i]. Over 75% of Estonian students embrace a growth mindset, believing in their capacity for intellectual development[ii]. This is in stark contrast with on average less than half of students in other countries sharing this same belief.

There are regular ‘brain breaks’ given to students to ensure readiness to learn. Several times in a lesson there will be a break where students are allowed to move around or play a game guided by the teacher[iii].

Whilst behaviour issues exist, disruptive students aren’t punished as the first port of call – a nurturing approach is preferred if possible[iv]. Often if a student cannot handle being in normal classes, they are taught in separate, smaller groups. This contributes to the relaxed and cordial atmosphere found across Estonian schools[v].

The administrative burden on teachers is actively kept to a minimum in order to allow teaching staff to dedicate the majority of their time to teaching and learning[vi].

Estonian schools were early adopters of high levels of digital integration. Digital competence is central to teaching strategies, preparing students for a digital world. Students are taught how to solve problems using digital technology, and skills such as coding and robotics[vii]. IT is not treated as a separate subject so much as digital skills are incorporated across the curriculum[viii]. Everything from textbooks to communication with parents is digital too. Lessons are regularly delivered whereby students learn independently using computers.

Autonomy

Autonomy is fundamental to the success of the Estonian education system. Control is relinquished from politicians and given to schools.

Whilst national standards exist, there is almost complete freedom over how schools meet them[i]. Schools simply must commit to 8 points of agreement like developing a scientific mindset, digital teaching and promoting the unique abilities of students[ii]. In meeting these standards, the only requirements are a small set of aligned textbooks, curriculum materials, national sampling assessments and limited high stakes exit exams[iii].

Schools are given autonomy over curriculum design, with 20% being designed by individual school management[iv]. They also choose their own goals and focus of studies. Principals decide on budget allocations, personnel, and make their own evaluations over teacher training requirements[v].

Teachers are highly respected in Estonia and the profession is seen as a creative endeavour. As such trust, and in turn freedom, are allowed over delivery of lessons in tandem with the minimally prescriptive national curriculum[vi]. Teachers decide the appropriate textbooks and teaching methods in accordance with what they view as most likely to engage their students[vii].

Inspections by Government agencies are far less intrusive than international counterparts like Ofsted in the UK. There is no separate inspectorate, and no full-scale inspections are carried out[viii]. Inspections are only for administration or in case of complaints and are not concerned with teaching and learning[ix]. The system of evaluation is not highly stringent and the freedom which this allows contributes to the wider systems success. Inspections are seen as a support and consultation service for schools in their areas of weakness. There is no culture of fear around this process, which is often led by teachers themselves[x]. Following a review of the problems experienced, the inspector calls another school leader who has experienced similar problems, who then advises the struggling school[xi]. As such school inspections collect data regularly over policies that may or not be working, and from here simply recommend evidence-based changes[xii].

High Quality Teachers

Another key contributor to the success of Estonia is the high quality of their skilled teachers.

All teachers are highly educated and required to hold a master’s degree[i]. As such teacher compensation has been rising steadily, with salaries expected to reach 120% of the national average in 2024.[ii]

Ongoing professional development is given great importance in school policy, and 1% of each school’s budget is earmarked for this[iii]. Schools hold autonomy over how they carry out this development based on their respective needs[iv].

Free time is reserved for teachers to collaborate and share best practice with colleagues from within their school and other schools too[v]. This ensures no school lags behind and that students benefit from the collective knowledge of all Estonian teachers.

Holistic Approaches to Education

Despite excelling in academic subjects, Estonia takes a more holistic approach to education than most nations.

Another focus of Bridget Phillipson’s visit to Estonia was their extensive state funded hobby schools. These free after school clubs support children’s education and offer parents flexibility if they have to work late[i]. Encouraging young people to get involved in hobbies is seen to help develop them into good citizens through the skills and joy gained. Instruction is provided in areas like sports, technology, culture, nature and music. For example, specialists from universities may work with students on a weekly basis on projects like the development of a satellite that will eventually be launched into space[ii]. Students get credit for participation that then contributes towards graduating school.

Within school, skills beyond the traditionally academic are given higher value. Social and personal skills are taught. Creative and physical subjects foster a sense of wellbeing and accomplishment, ranging from arts and music to technology and sports. The heightened focus on these subjects develops vital skills for later life like teamwork, communication and problem solving[iii]. Students learn to see the joy in education whilst developing these key skills, and this form of learning is seen as better than just the traditional way of sitting in a classroom and listening[iv].

This links into a national drive to shift teaching and learning towards 8 competencies including social skills, creativity and entrepreneurship[v]. In accordance, the Government has also changed the secondary school exit requirement away from 5 core subjects to instead include a creative research or practical project. Students learn practical skills from projects like conducting their own experiments or surveys.

After basic school, vocational education is given a high-level status alongside the traditional academic routes. These see close collaborations with local companies to develop practical skills, with later opportunities for apprenticeships[vi].

Historical and Cultural Factors Behind Success

The context of Estonia as a nation is a key determinant of their success in education and might make this success somewhat difficult to replicate in other nations.

Estonia has historically seen a strong education system as being key to preserving a sense of national identity through many occupations, most recently under the Soviet Union[i]. This has fostered a national desire to see every individual perform to their best, with education a key means towards this end[ii].

Much like in Germany, Estonians have a tradition for hard work and a methodical approach[iii]. As such students are more willing to spend hours studying. This plays into a wider context of Estonia being an entrepreneurial nation with a fast-growing economy[iv]. Despite being a small country, Estonia is an international tech hub, being home to giants like Skype and Wise[v]. There is a culture of wanting to prove themselves and this begins with education.

The nation being so small lends itself to the success of the inspection system, with leaders in education being well acquainted with one another. Powerful localised social networks exist as a result, enabling best practice sharing and support[vi].

Challenges to Continued Success

Despite its successes, the Estonian education system is not without its challenges.

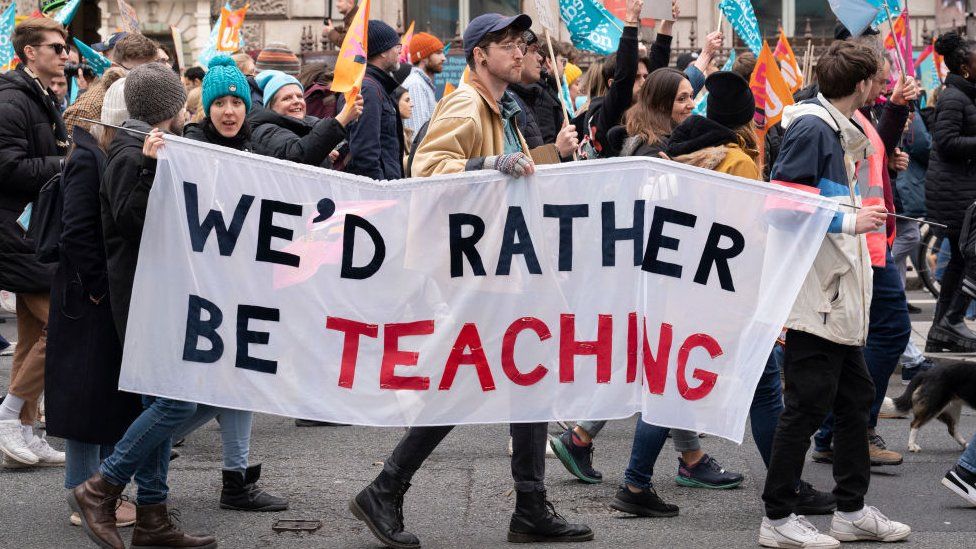

Chief among these is a lack of teachers. 73% of students are in schools where the quality of instruction was limited by a lack of teaching staff in 2022[i]. This figure is far higher than the 44% reported in 2018, indicating a worsening problem. The problem is fuelled by workload and recruitment issues[ii]. Teaching salaries are among the lowest in Europe[iii]. This joined with the fact that there are limited progression opportunities and that every teacher is required to hold a Masters degree, means many teachers look to other career routes[iv]. Teachers held their first strike in 2024[v]. But amidst an economic recession and the Ukraine crisis seeing education funds being diverted to defence, ongoing efforts to increase teacher salaries have stalled[vi].

Half of teachers are also over 50 years old, and whilst these teachers can be credited with upholding the Estonian success story, the current recruitment crisis threatens continued success[vii].

The latest PISA results showed a pattern of initial performance rises followed by a continual decline to 2022. There is also a growing gap between high achievers and low achievers in the country. In Mathematics, all learners became weaker, but low achievers declined at a faster rate than high achievers[viii]. Furthermore, compared to 2012, the number of learners scoring lower than the baseline proficiency grew considerably.

Final Thoughts

The case of Estonia is admirable, and we can only hope that Bridget Phillipson will seek to emulate some of the roots of their success in the UK.

The Secretary of State has already indicated her desire to improve the provision of early years education, but this must now be implemented.

Trust between education and the state has been broken during the last 14 years of Conservative Government. This can be remedied by granting more autonomy to individual schools and ensuring inspections actively seek to support, rather than reprimand schools.

We also must actively improve the quality of teachers across the UK through a heightened focus on teacher training and greater opportunities for professional development.

Educators must also be allowed to teach a curriculum that expands beyond the narrow remit prescribed by the previous Government. As in Estonia, all students should be allowed to discover their strengths and to develop skills beyond what traditional subjects can allow.

The UK education system long been plagued by inequality, where entry into private or selective schools predicts outsized success. We must seek to improve the quality of state schools and allow them to be a vehicle to a more equal, thriving society.

But there are warning signs from this trailblazing nation too. Policymakers in the UK should be weary of taking teachers for granted. Reducing workload and increasing pay in line with the strenuous job expected of them should be a priority. Further, the UK has seen improvements in their PISA results too, but Estonia serves as a reminder not to grow complacent with any successes and instead to continually seek to progress the system.

With the UK placing 12th in the latest PISA results, there is no reason that we cannot strive to be at the same level as Estonia the next time results are recorded.

Estonia should serve as a source of inspiration and learning for all educators, in the same spirit in which their educators continually seek to learn from one another. Following their steps to success can only lead to a greater quality of education for all.

[i] PISA

[ii] G1

[iii] GRE

[iv] G1

[v] G1

[vi] G1

[vii] INT

[viii] PISA

[i] G1

[ii] GRE

[iii] INT

[iv] BBC

[v] GRE

[vi] INT

[i] G2

[ii] INT

[iii] G1

[iv] G1

[v] INT

[vi] EDU

[i] G1

[ii] INV

[iii] EDU

[iv] IRE

[v] IRE

[i] G1

[ii] INT

[iii] INT

[iv] IRE

[v] EDU

[vi] GRE

[vii] EDU

[viii] INT

[ix] IRE

[x] GRE

[xi] INT

[xii] IRE

[i] IRE

[ii] INV

[iii] G1

[iv] G1

[v] G1

[vi] INT

[vii] EDU

[viii] G1

[i] G1

[ii] INT

[iii] GRE

[iv] INT

[v] EDU

[vi] G1

[vii] EDU

[viii] BBC

[i] G1:

[ii] G1:

[iii] G1

[iv] EDU

[v] INT

[vi] INT

[vii] BBC

[viii] IRE

[ix] IRE

[x] G2

[xi] IRE

[xii] INT

[xiii] GRE

[xiv] BBC

[i] G1

[ii] INT

[iii] PISA

[iv] PISA

[v] INT